Writings

of H P Blavatsky

Cardiff Theosophical Society in Wales

206 Newport Road, Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 -1DL

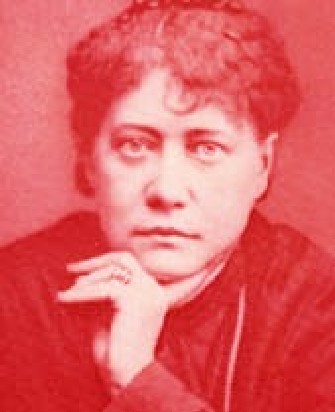

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831 – 1891)

The Founder of Modern Theosophy

Have Animals Souls

By

H

P Blavatsky

Continually

soaked with blood, the whole earth is but an immense altar upon which all that

lives has to be immolated--endlessly, incessantly. . . .

--COMTE JOSEPH

DE MAISTRE (Soirées I. ii, 35)

MANY are the

"antiquated religious superstitions" of the East which Western

nations often and unwisely deride: but none is so laughed at and practically

set at defiance as the great respect of Oriental people for animal life.

Flesh-eaters cannot sympathize with total abstainers from meat. We Europeans

are nations of civilized barbarians with but a few millenniums between

ourselves and our cave-dwelling forefathers who sucked the blood and marrow

from uncooked bones. Thus, it is only natural that those who hold human life so

cheaply in their frequent and often iniquitous wars, should entirely disregard

the death-agonies of the brute creation, and daily sacrifice millions of

innocent, harmless lives; for we are too epicurean to devour tiger steaks or

crocodile cutlets, but must have tender lambs and golden feathered pheasants.

All this is only as it should be in our era of Krupp cannons and scientific

vivisectors. Nor is it a matter of great wonder that the hardy European should

laugh at the mild Hindu, who shudders at the bare thought of killing a cow, or

that he should refuse to sympathize with the Buddhist and Jain, in their

respect for the life of every sentient creature--from the elephant to the gnat.

But, if

meat-eating has indeed become a vital necessity--"the tyrant's

plea!"--among Western nations; if hosts of victims in every city, borough

and village of the civilized world must needs be daily slaughtered in temples

dedicated to the deity, denounced by St. Paul and worshipped by men "whose

God is their belly":--if all this and much more cannot be avoided in our

"age of Iron," who can urge the same excuse for sport? Fishing,

shooting, and hunting, the most fascinating of all the "amusements"

of civilized life--are certainly the most objectionable from the standpoint of

occult philosophy, the most sinful in the eyes of the followers of these

religious systems which are the direct outcome of the Esoteric

Doctrine--Hinduism and Buddhism. Is it altogether without any good reason that

the adherents of these two religions, now the oldest in the world, regard the

animal world--from the huge quadruped down to the infinitesimally small

insect--as their "younger brothers," however ludicrous the idea to a

European? This question shall receive due consideration further on.

Nevertheless,

exaggerated as the notion may seem, it is certain that few of us are able to

picture to ourselves without shuddering the scenes which take place early every

morning in the innumerable shambles of the so-called civilized world, or even

those daily enacted during the "shooting season." The first sun-beam

has not yet awakened slumbering nature, when from all points of the compass

myriads of hecatombs are being prepared--to salute the rising luminary. Never

was heathen Moloch gladdened by such a cry of agony from his victims as the

pitiful wail that in all Christian countries rings like a long hymn of

suffering throughout nature, all day and every day from morning until evening.

In ancient Sparta--than whose stern citizens none were ever less sensitive to

the delicate feelings of the human heart--a boy, when convicted of torturing an

animal for amusement, was put to death as one whose nature was so thoroughly

villainous that he could not be permitted to live. But in civilized Europe

rapidly progressing in all things save Christian virtues--might remains unto

this day the synonym of right. The entirely useless, cruel practice of shooting

for mere sport countless hosts of birds and animals is nowhere carried on with

more fervour than in Protestant England, where the merciful teachings of Christ

have hardly made human hearts softer than they were in the days of Nimrod,

"the mighty hunter before the Lord." Christian ethics are as

conveniently turned into paradoxical syllogisms as those of the

"heathen." The writer was told one day by a sportsman that since

"not a sparrow falls on the ground without the will of the Father,"

he who kills for sport--say, one hundred sparrows does thereby one hundred

times over--his Father's will!

A wretched lot

is that of poor brute creatures, hardened as it is into implacable fatality by

the hand of man. The rational soul of the human being seems born to become the

murderer of the irrational soul of the animal--in the full sense of the word,

since the Christian doctrine teaches that the soul of the animal dies with its

body. Might not the legend of Cain and Abel have had a dual signification? Look

at that other disgrace of our cultured age--the scientific slaughter-houses

called "vivisection rooms." Enter one of those halls in Paris, and behold

Paul Bert, or some other of these men--so justly called "the learned

butchers of the Institute"--at his ghastly work. I have but to translate

the forcible description of an eye-witness, one who has thoroughly studied the

modus operandi of those "executioners," a well known French author:

"Vivisection"--he

says--"is a specialty in which torture, scientifically economised by our

butcher-academicians, is applied during whole days, weeks, and even months to

the fibres and muscles of one and the same victim. It (torture) makes use of

every and any kind of weapon, performs its analysis before a pitiless audience,

divides the task every morning between ten apprentices at once, of whom one

works on the eye, another one on the leg, the third on the brain, a fourth on the

marrow; and whose inexperienced hands succeed, nevertheless, towards night

after a hard day's work, in laying bare the whole of the living carcass they

had been ordered to chisel out, and that in the evening, is carefully stored

away in the cellar, in order that early next morning it may be worked upon

again if only there is a breath of life and sensibility left in the victim! We

know that the trustees of the Grammont law (loi) have tried to rebel against

this abomination; but Pans showed herself more inexorable than London and

Glasgow."l

And yet these

gentlemen boast of the grand object pursued, and of the grand secrets

discovered by them. "Horror and lies!"--exclaims the same author.

"In the matter of secrets--a few localizations of faculties and cerebral

motions excepted--we know but of one secret that belongs to them by rights: it

is the secret of torture eternalized, beside which the terrible natural law of

autophagy (mutual manducation), the horrors of war, the merry massacres of

sport, and the sufferings of the animal under the butcher's knife--are as

nothing! Glory to our men of science! They have surpassed every former kind of

torture, and remain now and for ever, without any possible contestation, the

kings of artificial anguish and despair!"2

The usual plea

for butchering, killing, and even for legally torturing animals--as in

vivisection--is a verse or two in the Bible, and its ill-digested meaning,

disfigured by the so-called scholasticism represented by Thomas Aquinas. Even

De Mirville, that ardent defender of the rights of the church, calls such

texts--"Biblical tolerances, forced from God after the deluge, as so many

others, and based upon the decadence of our strength." However this may

be, such texts are amply contradicted by others in the same Bible. The

meat-eater, the sportsman and even the vivisector--if there are among the last

named those who believe in special creation and the Bible--generally quote for

their justification that verse in Genesis, in which God gives dual

Adam--"dominion over the fish, fowl, cattle, and over every living thing

that moveth upon the earth"--(Ch. I., v. 28); hence--as the Christian

understands it--power of life and death over every animal on the globe. To this

the far more philosophical Brahman and Buddhist might answer; "Not so.

Evolution starts to mould future humanities within the lowest scales of being.

Therefore, by killing an animal, or even an insect, we arrest the progress of

an entity towards its final goal in nature--MAN"; and to this the student

of occult philosophy may say "Amen," and add that it not only retards

the evolution of that entity, but arrests that of the next succeeding human and

more perfect race to come.

Which of the

opponents is right, which of them the more logical? The answer depends mainly,

of course, on the personal belief of the intermediary chosen to decide the

questions. If he believes in special creation--so-called--then in answer to the

plain question--"Why should homicide be viewed as a most ghastly sin

against God and nature, and the murder of millions of living creatures be

regarded as mere sport?"--he will reply:--"Because man is created in

God's own image and looks upward to his Creator and to his birth-place--heaven

(os homini sublime dedit); and that the gaze of the animal is fixed downward on

its birth-place--the earth; for God said--'Let the earth bring forth the living

creature after his kind, cattle and creeping thing, and beast of the earth

after his kind'." (Genesis I, 24.) Again, "because man is endowed

with an immortal soul, and the dumb brute has no immortality, not even a short

survival after death."

Now to this an

unsophisticated reasoner might reply that if the Bible is to be our authority

upon this delicate question, there is not the slightest proof in it that man's

birth-place is in heaven anymore than that of the last of creeping

things--quite the contrary; for we find in Genesis that if God created

"man" and blessed "them," (Ch. I, v. 27-28) so he created

"great whales" and "blessed them" (2I, 22). Moreover,

"the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground" (II, v. 7): and

"dust" is surely earth pulverized? Solomon, the king and preacher, is

most decidedly an authority and admitted on all hands to have been the wisest

of the Biblical sages; and he gives utterances to a series of truths in

Ecclesiastes (Ch. III) which ought to have settled by this time every dispute

upon the subject. "The sons of men . . . might see that they themselves

are beasts" (v. 18) . . . "that which befalleth the sons of men,

befalleth the beasts . . . a man has no pre-eminence above a beast,"--(v.

19) "all go into one place; all are of the dust and turn to dust again,

(v. 20) . . . "who knoweth the spirit of man that goeth upwards, and the

spirit of the beast, that goeth downward to the earth? (v. 21.) Indeed,

"who knoweth!" At any rate it is neither science nor "school

divine."

Were the object

of these lines to preach vegetarianism on the authority of Bible or Veda, it would

be a very easy task to do so. For, if it is quite true that God gave dual

Adam--the "male and female" of Chapter I of Genesis--who has little

to do with our henpecked ancestor of Chapter II--"dominion over every

living thing," yet we nowhere find that the "Lord God" commanded

that Adam or the other to devour animal creation or destroy it for sport. Quite

the reverse. For pointing to the vegetable kingdom and the "fruit of a

tree yielding seed"--God says very plainly: "to you (men) it shall be

for meat." (I, 29.)

So keen was the

perception of this truth among the early Christians that during the first

centuries they never touched meat. In Octavio Tertullian writes to Minutius

Felix: "we are not permitted either to witness, or even hear narrated

(novere) a homicide, we Christians, who refuse to taste dishes in which animal

blood may have been mixed."

But the writer

does not preach vegetarianism, simply defending "animal rights" and

attempting to show the fallacy of disregarding such rights on Biblical authority.

Moreover, to argue with those who would reason upon the lines of erroneous

interpretations would be quite useless. One who rejects the doctrine of

evolution will ever find his way paved with difficulties; hence, he will never

admit that it is far more consistent with fact and logic to regard physical man

merely as the recognized paragon of animals, and the spiritual Ego that informs

him as a principle midway between the soul of the animal and the deity. It

would be vain to tell him that unless he accepts not only the verses quoted for

his justification but the whole Bible in the light of esoteric philosophy,

which reconciles the whole mass of contradictions and seeming absurdities in

it--he will never obtain the key to the truth;--for he will not believe it. Yet

the whole Bible teems with charity to men and with mercy and love to animals.

The original Hebrew text of Chapter XXIV of Leviticus is full of it. Instead of

the verses 17 and 18 as translated in the Bible: "And he that killeth a

beast shall make it good, beast for beast" in the original it

stands:--"life for life," or rather "soul for soul,"

nephesh tachat nephesh.3 And if the rigour of the law did not go to the extent

of killing, as in Sparta, a man's "soul" for a beast's

"soul"--still, even though he replaced the slaughtered soul by a

living one, a heavy additional punishment was inflicted on the culprit.

But this was

not all. In Exodus (Ch. XX. 10, and Ch. XXIII. 2 et seq.) rest on the Sabbath

day extended to cattle and every other animal. "The seventh day is the

sabbath . . . thou shalt not do any work, thou nor thy . . . cattle"; and

the Sabbath year . . . "the seventh year thou shalt let it (the land) rest

and lie still . . . that thine ox and thine ass may rest"--which

commandment, if it means anything, shows that even the brute creation was not

excluded by the ancient Hebrews from a participation in the worship of their

deity, and that it was placed upon many occasions on a par with man himself.

The whole question rests upon the misconception that "soul," nephesh,

is entirely distinct from "spirit"--ruach. And yet it is clearly

stated that "God breathed into the nostrils (of man) the breath of life

and man became a living soul," nephesh, neither more or less than an

animal, for the soul of an animal is also called nephesh. It is by development

that the soul becomes spirit, both being the lower and the higher rungs of one

and the same ladder whose basis is the UNIVERSAL SOUL or spirit.

This statement

will startle those good men and women who, however much they may love their

cats and dogs, are yet too much devoted to the teachings of their respective

churches ever to admit such a heresy. "The irrational soul of a dog or a

frog divine and immortal as our own souls are?"--they are sure to exclaim

but so they are. It is not the humble writer of the present article who says

so, but no less an authority for every good Christian than that king of the

preachers--St. Paul. Our opponents who so indignantly refuse to listen to the

arguments of either modern or esoteric science may perhaps lend a more willing

ear to what their own saint and apostle has to say on the matter; the true

interpretation of whose words, moreover, shall be given neither by a

theosophist nor an opponent, but by one who was as good and pious a Christian

as any, namely, another saint--John Chrysostom--he who explained and commented

upon the Pauline Epistles, and who is held in the highest reverence by the

divines of both the Roman Catholic and the Protestant churches. Christians have

already found that experimental science is not on their side; they may be still

more disagreeably surprised upon finding that no Hindu could plead more

earnestly for animal life than did St. Paul in writing to the Romans. Hindus

indeed claim mercy to the dumb brute only on account of the doctrine of

transmigration and hence of the sameness of the principle or element that

animates both man and brute. St. Paul goes further: he shows the animal hoping

for, and living in the expectation of the same "deliverance from the bonds

of corruption" as any good Christian. The precise expressions of that

great apostle and philosopher will be quoted later on in the present Essay and

their true meaning shown.

The fact that

so many interpreters--Fathers of the Church and scholastics,--tried to evade

the real meaning of St. Paul is no proof against its inner sense, but rather

against the fairness of the theologians whose inconsistency will be shown in

this particular. But some people will support their propositions, however

erroneous, to the last. Others, recognizing their earlier mistake, will, like

Cornelius a Lapide, offer the poor animal amende honorable. Speculating upon

the part assigned by nature to the brute creation in the great drama of life,

he says: "The aim of all creatures is the service of man. Hence, together

with him (their master) they are waiting for their renovation"--cum homine

renovationem suam expectant.4 "Serving" man, surely cannot mean being

tortured, killed, uselessly shot and otherwise misused; while it is almost

needless to explain the word "renovation." Christians understand by

it the renovation of bodies after the second coming of Christ; and limit it to

man, to the exclusion of animals. The students of the Secret Doctrine explain

it by the successive renovation and perfection of forms on the scale of

objective and subjective being, and in a long series of evolutionary

transformations from animal to man, and upward. . . .

This will, of

course, be again rejected by Christians with indignation. We shall be told that

it is not thus that the Bible was explained to them, nor can it ever mean that.

It is useless to insist upon it. Many and sad in their results were the

erroneous interpretations of that which people are pleased to call the "Word

of God." The sentence "cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall

he be unto his brethren" (Gen. IX, 25),--generated centuries of misery and

undeserved woe for the wretched slaves--the negroes. It is the clergy of the

United States who were their bitterest enemies in the anti-slavery question,

which question they opposed Bible in hand. Yet slavery is proved to have been

the cause of the natural decay of every country; and even proud Rome fell

because "the majority in the ancient world were slaves," as Geyer

justly remarks. But so terribly imbued at all times were the best, the most

intellectual Christians with those many erroneous interpretations of the Bible,

that even one of their grandest poets, while defending the right of man to

freedom, allots no such portion to the poor animal.

God gave us

only over beast, fish, fowl,

Dominion absolute; that right we hold

By his donation; but man over man

He made not lord; such title to himself

Reserving, human left from human free

--says Milton.

But, like

murder, error "will out," and incongruity must unavoidably occur

whenever erroneous conclusions are supported either against or in favour of a

prejudged question. The opponents of Eastern philozoism thus offer their

critics a formidable weapon to upset their ablest arguments by such incongruity

between premises and conclusions, facts postulated and deductions made.

It is the

purpose of the present Essay to throw a ray of light upon this most serious and

interesting subject. Roman Catholic writers in order to support the genuineness

of the many miraculous resurrections of animals produced by their saints, have

made them the subject of endless debates. The "soul in animals" is,

in the opinion of Bossuet, "the most difficult as the most important of

all philosophical questions."

Confronted with

the doctrine of the Church that animals, though not soulless, have no permanent

or immortal soul in them, and that the principle which animates them dies with

the body, it becomes interesting to learn how the school-men and the Church

divines reconcile this statement with that other claim that animals may be and

have been frequently and miraculously resurrected

Though but a

feeble attempt--one more elaborate would require volumes--the present Essay, by

showing the inconsistency of the scholastic and theological interpretations of

the Bible, aims at convincing people of the great criminality of

taking--especially in sport and vivisection--animal life. Its object, at any

rate, is to show that however absurd the notion that either man or brute can be

resurrected after the life-principle has fled from the body forever, such

resurrections--if they were true--would not be more impossible in the case of a

dumb brute than in that of a man; for either both are endowed by nature with

what is so loosely called by us "soul," or neither the one nor the

other is so endowed.

II

What a chimera

is man! what a confused chaos, what a subject of contradiction! a professed

judge of all things, and yet a feeble worm of the earth! the great depository

and guardian of truth, and yet ad mere huddle of uncertainty! the glory and the

scandal of the universe!

--PASCAL

We shall now

proceed to see what are the views of the Christian Church as to the nature of

the soul in the brute, to examine how she reconciles the discrepancy between

the resurrection of a dead animal and the assumption that its soul dies with

it, and to notice some miracles in connection with animals. Before the final

and decisive blow is dealt to that selfish doctrine, which has become so

pregnant with cruel and merciless practices toward the poor animal world, the

reader must be made acquainted with the early hesitations of the Fathers of the

Patristic age themselves, as to the right interpretation of the words spoken

with reference to that question by St. Paul.

It is amusing

to note how the Karma of two of the most indefatigable defenders of the Latin

Church--Messrs. Des. Mousseaux and De Mirville, in whose works the record of

the few miracles here noted are found--led both of them to furnish the weapons

now used against their own sincere but very erroneous views.5

The great

battle of the Future having to be fought out between the "Creationists"

or the Christians, as all the believers in a special creation and a personal

god, and the Evolutionists or the Hindus, Buddhists, all the Free-thinkers and

last, though not least, most of the men of science, a recapitulation of their

respective positions is advisable.

1. The

Christian world postulates its right over animal life: (a) on the afore-quoted

Biblical texts and the later scholastic interpretations; (b) on the assumed

absence of anything like divine or human soul in animals. Man survives death,

the brute does not.

2. The Eastern

Evolutionists, basing their deductions upon their great philosophical systems,

maintain it is a sin against nature's work and progress to kill any living

being--for reasons given in the preceding pages.

3. The Western

Evolutionists, armed with the latest discoveries of science, heed neither

Christians nor Heathens. Some scientific men believe in Evolution, others do

not. They agree, nevertheless, upon one point: namely, that physical, exact

research offers no grounds for the presumption that man is endowed with an

immortal, divine soul, any more than his dog.

Thus, while the

Asiatic Evolutionists behave toward animals consistently with their scientific

and religious views, neither the church nor the materialistic school of science

is logical in the practical applications of their respective theories. The

former, teaching that every living thing is created singly and specially by

God, as any human babe may be, and that it finds itself from birth to death

under the watchful care of a wise and kind Providence, allows the inferior

creation at the same time only a temporary soul. The latter, regarding both man

and animal as the soulless production of some hitherto undiscovered forces in

nature, yet practically creates an abyss between the two. A man of science, the

most determined materialist, one who proceeds to vivisect a living animal with

the utmost coolness, would yet shudder at the thought of laming--not to speak

of torturing to death--his fellow man. Nor does one find among those great

materialists who were religiously inclined men any who have shown themselves

consistent and logical in defining the true moral status of the animal on this

earth and the rights of man over it.

Some instances

must now be brought to prove the charges stated. Appealing to serious and

cultured minds it must be postulated that the views of the various authorities

here cited are not unfamiliar to the reader. It will suffice therefore simply

to give short epitomes of some of the conclusions they have arrived

at--beginning with the Churchmen.

As already

stated, the Church exacts belief in the miracles performed by her great Saints.

Among the various prodigies accomplished we shall choose for the present only

those that bear directly upon our subject--namely, the miraculous resurrections

of dead animals. Now one who credits man with an immortal soul independent of

the body it animates can easily believe that by some divine miracle the soul

can be recalled and forced back into the tabernacle it deserts apparently for

ever. But how can one accept the same possibility in the case of an animal,

since his faith teaches him that the animal has no independent soul, since it

is annihilated with the body? For over two hundred years, ever since Thomas of Aquinas,

the Church has authoritatively taught that the soul of the brute dies with its

organism. What then is recalled back into the clay to reanimate it? It is at

this juncture that scholasticism steps in, and--taking the difficulty in

hand--reconciles the irreconcilable.

It premises by

saying that the miracles of the Resurrection of animals are numberless and as

well authenticated as "the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ."6

The Bollandists give instances without number. As Father Burigny, a hagiographer

of the 17th century, pleasantly remarks concerning the bustards resuscitated by

St. Remi--"I may be told, no doubt, that I am a goose myself to give

credence to such 'blue bird' tales. I shall answer the joker, in such a case,

by saying that, if he disputes this point, then must he also strike out from

the life of St. Isidore of Spain the statement that he resuscitated from death

his master's horse; from the biography of St. Nicolas of Tolentino--that he

brought back to life a partridge, instead of eating it; from that of St.

Francis--that he recovered from the blazing coals of an oven, where it was

baking, the body of a lamb, which he forthwith resurrected; and that he also

made boiled fishes, which he resuscitated, swim in their sauce; etc., etc. Above

all he, the sceptic, will have to charge more than 100,000 eye-witnesses--among

whom at least a few ought to be allowed some common sense--with being either

liars or dupes."

A far higher

authority than Father Burigny, namely, Pope Benedict (Benoit) XIV, corroborates

and affirms the above evidence. The names, moreover, as eye-witnesses to the

resurrections, of Saint Sylvestrus, Francois de Paule, Severin of Cracow and a

host of others are all mentioned in the Bollandists. "Only he

adds"--says Cardinal de Ventura who quotes him--"that, as

resurrection, however, to deserve the name requires the identical and numerical

reproduction of the form,7 as much as of the material of the dead creature; and

as that form (or soul) of the brute is always annihilated with its body

according to St. Thomas' doctrine, God, in every such case finds himself

obliged to create for the purpose of the miracle a new form for the resurrected

animal; from which it follows that the resurrected brute was not altogether

identical with what it had been before its death (non idem omnino esse.)"8

Now this looks

terribly like one of the mayas of magic. However, although the difficulty is

not absolutely explained, the following is made clear: the principle, that

animated the animal during its life,. and which is termed soul, being dead or

dissipated after the death of the body, another soul--"a kind of an

informal soul"--as the Pope and the Cardinal tell us--is created for the

purpose of miracle by God; a soul, moreover, which is distinct from that of

man, which is "an independent, ethereal and ever lasting entity."

Besides the

natural objection to such a proceeding being called a "miracle"

produced by the saint, for it is simply God behind his back who

"creates" for the purpose of his glorification an entirely new soul

as well as a new body, the whole of the Thomasian doctrine is open to

objection. For, as Descartes very reasonably remarks: "if the soul of the

animal is so distinct (in its immateriality) from its body, we believe it

hardly possible to avoid recognizing it as a spiritual principle, hence--an

intelligent one."

The reader need

hardly be reminded that Descartes held the living animal as being simply an

automaton, a "well wound up clock-work," according to Malebranche.

One, therefore, who adopts the Cartesian theory about the animal would do as

well to accept at once the views of the modern materialists. For, since that

automaton is capable of feelings, such as love, gratitude, etc., and is endowed

as undeniably with memory, all such attributes must be as materialism teaches

us "properties of matter." But if the animal is an

"automaton," why not Man? Exact science-- anatomy, physiology,

etc.,--finds not the smallest difference between the bodies of the two; and who

knows justly enquires Solomon--whether the spirit of man "goeth

upward" any more than that of the beast? Thus we find metaphysical

Descartes as inconsistent as any one.

But what does

St. Thomas say to this? Allowing a soul (anima) to the brute, and declaring it

immaterial, he refuses it at the same time the qualification of spiritual.

Because, he says: "it would in such case imply intelligence, a virtue and

a special operation reserved only for the human soul." But as at the

fourth Council of Lateran it had been decided that "God had created two

distinct substances, the corporeal (mundanam) and the spiritual (spiritualem),

and that something incorporeal must be of necessity spiritual St. Thomas had to

resort to a kind of compromise, which can avoid being called a subterfuge only

when performed by a saint. He says: "This soul of the brute is neither

spirit, nor body; it is of a middle nature."9 This is a very unfortunate

statement. For elsewhere, St. Thomas says that "all the souls--even those

of plants--have the substantial form of their bodies," and if this is true

of plants, why not of animals? It is certainly neither "spirit" nor

pure matter, but of that essence which St. Thomas calls "a middle

nature." But why, once on the right path, deny it survivance--let alone

immortality? The contradiction is so flagrant that De Mirville in despair

exclaims, "Here we are, in the presence of three substances, instead of

the two, as decreed by the Lateran Council!", and proceeds forthwith to

contradict, as much as he dares, the "Angelic Doctor."

The great

Bossuet in his Traité de la Connaissance de Dieu et de soi même analyses and

compares the system of Descartes with that of St. Thomas. No one can find fault

with him for giving the preference in the matter of logic to Descartes. He

finds the Cartesian "invention"--that of the automaton,--as

"getting better out of the difficulty" than that of St. Thomas,

accepted fully by the Catholic Church; for which Father Ventura feels indignant

against Bossuet for accepting "such a miserable and puerile error."

And, though allowing the animals a soul with all its qualities of affection and

sense, true to his master St. Thomas, he too refuses them intelligence and

reasoning powers. "Bossuet," he says, "is the more to be blamed,

since he himself has said: 'I foresee that a great war is being prepared

against the Church under the name of Cartesian philosophy'." He is right

there, for out of the "sentient matter" of the brain of the brute

animal comes out quite naturally Locke's thinking matter, and out of the latter

all the materialistic schools of our century. But when he fails, it is through

supporting St. Thomas' doctrine, which is full of flaws and evident

contradictions. For, if the soul of the animal is, as the Roman Church teaches,

an informal, immaterial principle, then it becomes evident that, being

independent of physical organism, it cannot "die with the animal" any

more than in the case of man. If we admit that it subsists and survives, in

what respect does it differ from the soul of man? And that it is eternal--once

we accept St. Thomas' authority on any subject--though he contradicts himself

elsewhere. "The soul of man is immortal, and the soul of the animal

perishes," he says (Summa, Vol. V. p. 164),--this, after having queried in

Vol. II of the same grand work (p. 256) "are there any beings that

re-emerge into nothingness?" and answered himself:--"No, for in the

Ecclesiastes it is said: (iii. 14) Whatsoever GOD doeth, it shall be for ever.

With God there is no variableness (James I. 17)." "Therefore,"

goes on St. Thomas, "neither in the natural order of things, nor by means

of miracles, is there any creature that re-emerges into nothingness (is

annihilated); there is naught in the creature that is annihilated, for that

which shows with the greatest radiance divine goodness is the perpetual

conservation of the creatures."l0

This sentence

is commented upon and confirmed in the annotation by the Abbé Drioux, his

translator. "No," he remarks--"nothing is annihilated; it is a

principle that has become with modern science a kind of axiom."

And, if so, why

should there be an exception made to this invariable rule in nature, recognized

both by science and theology,--only in the case of the soul of the animal? Even

though it had no intelligence, an assumption from which every impartial thinker

will ever and very strongly demur.

Let us see,

however, turning from scholastic philosophy to natural sciences, what are the

naturalist's objections to the animal having an intelligent and therefore an

independent soul in him.

"Whatever

that be, which thinks, which understands, which acts, it is something celestial

and divine; and upon that account must necessarily be eternal," wrote

Cicero, nearly two millenniums ago. We should understand well, Mr. Huxley

contradicting the conclusion,--St. Thomas of Aquinas, the "king of the

metaphysicians," firmly believed in the miracles of resurrection performed

by St. Patrick.l1

Really, when

such tremendous claims as the said miracles are put forward and enforced by the

Church upon the faithful, her theologians should take more care that their

highest authorities at least should not contradict themselves, thus showing

ignorance upon questions raised nevertheless to a doctrine.

The animal,

then, is debarred from progress and immortality, because he is an automaton.

According to Descartes, he has no intelligence, agreeably to mediæval

scholasticism; nothing but instinct, the latter signifying involuntary

impulses, as affirmed by the materialists and denied by the Church.

Both Frederic

and George Cuvier have discussed amply, however, on the intelligence and the

instinct in animals.l2 Their ideas upon the subject have been collected and

edited by Flourens, the learned Secretary of the Academy of Sciences. This is

what Frederic Cuvier, for thirty years the Director of the Zoological

Department and the Museum of Natural History at the Jardin des Plantes, Paris,

wrote upon the subject. "Descartes' mistake, or rather the general

mistake, lies in that no sufficient distinction was ever made between

intelligence and instinct. Buffon himself had fallen into such an omission, and

owing to it every thing in his Zoological philosophy was contradictory.

Recognizing in the animal a feeling superior to our own, as well as the

consciousness of its actual existence, he denied it at the same time thought,

reflection, and memory, consequently every possibility of having

thoughts." (Buffon, Discourse on the Nature of Animals, VII, p. 57.) But,

as he could hardly stop there, he admitted that the brute had a kind of memory,

active, extensive and more faithful than our (human) memory (Id. Ibid., p. 77).

Then, after having refused it any intelligence, he nevertheless admitted that

the animal "consulted its master, interrogated him, and understood

perfectly every sign of his will." (Id. Ibid., Vol. X, History of the Dog,

p. 2.)

A more

magnificent series of contradictory statements could hardly have been expected

from a great man of science.

The illustrious

Cuvier is right therefore in remarking in his turn, that "this new

mechanism of Buffon is still less intelligible than Descartes'

automaton."l3

As remarked by

the critic, a line of demarcation ought to be traced between instinct and

intelligence. The construction of beehives by the bees, the raising of dams by

the beaver in the middle of the naturalist's dry floor as much as in the river,

are all the deeds and effects of instinct forever unmodifiable and changeless,

whereas the acts of intelligence are to be found in actions evidently thought

out by the animal, where not instinct but reason comes into play, such as its

education and training calls forth and renders susceptible of perfection and

development. Man is endowed with reason, the infant with instinct; and the

young animal shows more of both than the child.

Indeed, every

one of the disputants knows as well as we do that it is so. If any materialist

avoid confessing it, it is through pride. Refusing a soul to both man and beast,

he is unwilling to admit that the latter is endowed with intelligence as well

as himself, even though in an infinitely lesser degree. In their turn the

churchman, the religiously inclined naturalist, the modern metaphysician,

shrink from avowing that man and animal are both endowed with soul and

faculties, if not equal in development and perfection, at least the same in

name and essence. Each of them knows, or ought to know that instinct and

intelligence are two faculties completely opposed in their nature, two enemies

confronting each other in constant conflict; and that, if they will not admit

of two souls or principles, they have to recognize, at any rate, the presence

of two potencies in the soul, each having a different seat in the brain, the localization

of each of which is well known to them, since they can isolate and temporarily

destroy them in turn--according to the organ or part of the organs they happen

to be torturing during their terrible vivisections. What is it but human pride

that prompted Pope to say:

Ask for whose end the heavenly bodies

shine;

Earth for whose use? Pride answers, 'Tis

for mine.

For me kind nature wakes her genial power,

Suckles each herb, and spreads out every

flower.

****

*

For

me the mine a thousand treasures brings;

For me health gushes from a thousand

springs;

Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me

rise;

My footstool earth, my canopy the skies!

And it is the

same unconscious pride that made Buffon utter his paradoxical remarks with

reference to the difference between man and animal. That difference consisted

in the "absence of reflection, for the animal," he says, "does

not feel that he feels." How does Buffon know? "It does not think

that it thinks," he adds, after having told the audience that the animal

remembered, often deliberated, compared and chose!l4 Who ever pretended that a

cow or a dog could be an idealogist? But the animal may think and know it

thinks, the more keenly that it cannot speak, and express its thoughts. How can

Buffon or any one else know? One thing is shown however by the exact

observations of naturalists and that is, that the animal is endowed with

intelligence; and once this is settled, we have but to repeat Thomas Aquinas'

definition of intelligence--the prerogative of man's immortal soul--to see that

the same is due to the animal.

But in justice

to real Christian philosophy, we are able to show that primitive Christianity

has never preached such atrocious doctrines--the true cause of the falling off

of so many of the best men as of the highest intellects from the teachings of

Christ and his disciples.

III

O Philosophy,

thou guide of life, and discoverer of virtue!

--

Philosophy is a

modest profession, it is all reality and plain dealing; I hate solemnity and

pretence, with nothing but pride at the bottom.

--PLINY

THE destiny of

man--of the most brutal, animal-like, as well as of the most saintly--being

immortality, according to theological teaching; what is the future destiny of

the countless hosts of the animal kingdom? We are told by various Roman

Catholic writers--Cardinal Ventura, Count de Maistre and many others--that

"animal soul is a Force."

"It is

well established that the soul of the animal," says their echo De

Mirville,--"was produced by the earth, for this is Biblical. All the

living and moving souls (nephesh or life principle) come from the earth; but,

let me be understood, not solely from the dust, of which their bodies as well

as our own were made, but from the power or potency of the earth; i.e., from

its immaterial force, as all forces are . . . those of the sea, of the air,

etc., all of which are those Elementary Principalities (principautés

élementaires) of which we have spoken elsewhere."l5

What the

Marquis de Mirville understands by the term is, that every "Element"

in nature is a domain filled and governed by its respective invisible spirits.

The Western Kabalists and the Rosicrucians named them Sylphs, Undines,

Salamanders and Gnomes; christian mystics, like De Mirville, give them Hebrew

names and class each among the various kinds of Demons under the sway of

Satan--with God's permission, of course.

He too rebels

against the decision of St. Thomas, who teaches that the animal soul is

destroyed with the body. "It is a force,"--he says--that "we are

asked to annihilate, the most substantial force on earth, called animal

soul," which, according to the Reverend Father Ventura, isl6 "the most

respectable soul after that of man."

He had just

called it an immaterial force, and now it is named by him "the most

substantial thing on earth."l7

But what is

this Force? George Cuvier and Flourens the academician tell us its secret.

"The form

or the force of the bodies," (form means soul in this case, let us

remember,) the former writes,--"is far more essential to them than matter

is, as (without being destroyed in its essence) the latter changes constantly,

whereas the form prevails eternally.' To this Flourens observes: "In

everything that has life, the form is more persistent than matter; for, that

which constitutes the BEING of the living body, its identity and its sameness,

is its form."l8

"Being,"

as De Mirville remarks in his turn, "a magisterial principle. a philosophical

pledge of our immortality,"l9 it must be inferred that soul--human and

animal--is meant under this misleading term. It is rather what we call the ONE

LIFE I suspect.

However this

may be, philosophy, both profane and religious, corroborates this statement

that the two "souls" are identical in man and beast. Leibnitz, the

philosopher beloved by Bossuet, appeared to credit "Animal

Resurrection" to a certain extent. Death being for him "simply the

temporary enveloping of the personality" he likens it to the preservation

of ideas in sleep, or to the butterfly within its caterpillar. "For

him," says De Mirville, "resurrection20 is a general law in nature,

which becomes a grand miracle, when performed by a thaumaturgist, only in

virtue of its prematurity, of the surrounding circumstances, and of the mode in

which he operates." In this Leibnitz is a true Occultist without

suspecting it. The growth and blossoming of a flower or a plant in five minutes

instead of several days and weeks, the forced germination and development of

plant, animal or man, are facts preserved in the records of the Occultists.

They are only seeming miracles; the natural productive forces hurried and a

thousand-fold intensified by the induced conditions under occult laws known to

the Initiate. The abnormally rapid growth is effected by the forces of nature,

whether blind or attached to minor intelligences subjected to man's occult

power, being brought to bear collectively on the development of the thing to be

called forth out of its chaotic elements. But why call one a divine miracle,

the other a satanic subterfuge or simply a fraudulent performance?

Still as a true

philosopher Leibnitz finds himself forced, even in this dangerous question of

the resurrection of the dead, to include in it the whole of the animal kingdom

in its great synthesis, and to say: "I believe that the souls of the

animals are imperishable, . . . and I find that nothing is better fitted to

prove our own immortal nature."2l

Supporting

Leibnitz, Dean, the Vicar of Middleton, published in 1748 two small volumes

upon this subject. To sum up his ideas, he says that "the holy scriptures

hint in various passages that the brutes shall live in a future life. This

doctrine has been supported by several Fathers of the Church. Reason teaching

us that the animals have a soul, teaches us at the same time that they shall

exist in a future state. The system of those who believe that God annihilates

the soul of the animal is nowhere supported, and has no solid foundation to

it," etc. etc.22

Many of the men

of science of the last century defended Dean's hypothesis, declaring it

extremely probable, one of them especially--the learned Protestant theologian

Charles Bonnet of Geneva. Now, this theologian was the author of an extremely

curious work called by him Palingenesia23 or the "New Birth," which

takes place, as he seeks to prove, owing to an invisible germ that exists in

everybody, and no more than Leibnitz can he understand that animals should be

excluded from a system, which, in their absence, would not be a unity, since

system means "a collection of laws."24

"The

animals," he writes, "are admirable books, in which the creator

gathered the most striking features of his sovereign intelligence. The

anatomist has to study them with respect, and, if in the least endowed with

that delicate and reasoning feeling that characterises the moral man, he will

never imagine, while turning over the pages, that he is handling slates or

breaking pebbles. He will never forget that all that lives and feels is

entitled to his mercy and pity. Man would run the risk of compromising his

ethical feeling were he to become familiarised with the suffering and the blood

of animals. This truth is so evident that Governments should never lose sight

of it. . . . as to the hypothesis of automatism I should feel inclined to

regard it as a philosophical heresy, very dangerousfor society, if it did not

so strongly violate good sense and feeling as to become harmless, for it can

never be generally adopted."

"As to the

destiny of the animal, if my hypothesis be right, Providence holds in reserve

for them the greatest compensations in future states.25 . . . And for me, their

resurrection is the consequence of that soul or form we are necessarily obliged

to allow them, for a soul being a simple substance, can neither be divided, nor

decomposed, nor yet annihilated. One cannot escape such an inference without

falling back into Descartes' automatism; and then from animal automatism one

would soon and forcibly arrive at that of man" . . .

Our modern

school of biologists has arrived at the theory of "automaton-man,"

but its disciples may be left to their own devices and conclusions. That with

which I am at present concerned, is the final and absolute proof that neither

the Bible, nor its most philosophical interpreters--however much they may have

lacked a clearer insight into other questions--have ever denied, on Biblical

authority, an immortal soul to any animal, more than they have found in it

conclusive evidence as to the existence of such a soul in man--in the old

Testament. One has but to read certain verses in Job and the Ecclesiastes (iii.

17 et seq. 22) to arrive at this conclusion. The truth of the matter is, that

the future state of neither of the two is therein referred to by one single

word. But if, on the other hand, only negative evidence is found in the Old

Testament concerning the immortal soul in animals, in the New it is as plainly

asserted as that of man himself, and it is for the benefit of those who deride

Hindu philozoism, who assert their right to kill animals at their will and

pleasure, and deny them an immortal soul, that a final and definite proof is

now being given.

St. Paul was

mentioned at the end of Part I as the defender of the immortality of all the brute

creation. Fortunately this statement is not one of those that can be

pooh-poohed by the Christians as "the blasphemous and heretical

interpretations of the holy writ, by a group of atheists and

free-thinkers." Would that every one of the profoundly wise words of the

Apostle Paul--an Initiate whatever else he might have been--was as clearly

understood as those passages that relate to the animals. For then, as will be

shown, the indestructibility of matter taught by materialistic science; the law

of eternal evolution, so bitterly denied by the Church; the omnipresence of the

ONE LIFE, or the unity of the ONE ELEMENT, and its presence throughout the

whole of nature as preached by esoteric philosophy, and the secret sense of St.

Paul's remarks to the Romans (viii. 18-23 ), would be demonstrated beyond doubt

or cavil to be obviously one and the same thing. Indeed, what else can that

great historical personage, so evidently imbued with neo-Platonic Alexandrian

philosophy, mean by the following, which I transcribe with comments in the

light of occultism, to give a clearer comprehension of my meaning?

The apostle

premises by saying (Romans viii. 16, 17) that "The spirit itself"

(Paramatma) "beareth witness with our spirit" (atman) "that we

are the children of God," and "if children, then heirs"--heirs

of course to the eternity and indestructibility of the eternal or divine

essence in us. Then he tells us that:

"The

sufferings of the present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which

shall be revealed." (v. 18.)

The

"glory" we maintain, is no "new Jerusalem," the symbolical

representation of the future in St. John's kabalistical Revelations--but the

Devachanic periods and the series of births in the succeeding races when, after

every new incarnation we shall find ourselves higher and more perfect,

physically as well as spiritually; and when finally we shall all become truly

the "sons" and "the children of God" at the "last

Resurrection"--whether people call it Christian, Nirvanic or Parabrahmic;

as all these are one and the same. For truly--

"The

earnest expectation of the creature waiteth for the manifestation of the sons

of God." (v. 19.)

By creature,

animal is here meant, as will be shown further on upon the authority of St. John

Chrysostom.But who are the "sons of God," for the manifestation of

whom the whole creation longs? Are they the "sons of God" with whom

"Satan came also" (see Job) or the "seven angels" of

Revelations? Have they reference to Christians only or to the "sons of

God" all over the world?26 Such "manifestation" is promised at

the end of every Manvantara27 or world-period by the scriptures of every great

Religion, and save in the Esoteric interpretation of all these, in none so

clearly as in the Vedas. For there it is said that at the end of each

Manvantara comes the pralaya, or the destruction of the world--only one of

which is known to, and expected by, the Christians--when there will be left the

Sishtas, or remnants, seven Rishis and one warrior, and all the seeds, for the

next human "tide-wave of the following Round."28 But the main

question with which we are concerned is not at present, whether the Christian

or the Hindu theory is the more correct; but to show that the Brahmins--in

teaching that the seeds of all the creatures are left over, out of the total

periodical and temporary destruction of all visible things, together with the

"sons of God" or the Rishis, who shall manifest themselves to future

humanity--say neither more nor less than what St. Paul himself preaches. Both

include all animal life in the hope of a new birth and renovation in a more

perfect state when every creature that now "waiteth" shall rejoice in

the "manifestation of the sons of God." Because, as St. Paul explains:

"The

creature itself (ipsa) also shall be delivered from the bondage of

corruption," which is to say that the seed or the indestructible animal

soul, which does not reach Devachan while in its elementary or animal state,

will get into a higher form and go on, together with man, progressing into

still higher states and forms, to end, animal as well as man, "in the

glorious liberty of the children of God" (v. 21).

And this

"glorious liberty" can be reached only through the evolution or the

Karmic progress of all creatures. The dumb brute having evoluted from the half

sentient plant, is itself transformed by degrees into man, spirit, God--et seq.

and ad infinitum! For says

"We know

("we," the Initiates) that the whole creation, (omnis creatura or

creature, in the Vulgate) groaneth and travaileth (in child-birth) in pain

until now."29 (v. 22.)

This is plainly

saying that man and animal are on a par on earth, as to suffering, in their

evolutionary efforts toward the goal and in accordance with Karmic law. By

"until now," is meant up to the fifth race. To make it still plainer,

the great Christian Initiate explains by saying:

"Not only

they (the animals) but ourselves also, which have the first-fruits of the

Spirit, we groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the

redemption of our body." (v. 23.) Yes, it is we, men, who have the

"first-fruits of the Spirit," or the direct Parabrahmic light, our

Atma or seventh principle, owing to the perfection of our fifth principle

(Manas), which is far less developed in the animal. As a compensation, however,

their Karma is far less heavy than ours. But that is no reason why they too

should not reach one day that perfection that gives the fully evoluted man the

Dhyanchohanic form.

Nothing could

be clearer--even to a profane, non-initiated critic--than those words of the

great Apostle, whether we interpret them by the light of esoteric philosophy,

or that of mediæval scholasticism. The hope of redemption, or, of the survival

of the spiritual entity, delivered "from the bondage of corruption,"

or the series of temporary material forms, is for all living creatures, not for

man alone.

But the

"paragon" of animals, proverbially unfair even to his fellow-beings,

could not be expected to give easy consent to sharing his expectations with his

cattle and domestic poultry. The famous Bible commentator, Cornelius a Lapide,

was the first to point out and charge his predecessors with the conscious and

deliberate intention of doing all they could to avoid the application of the word

creatura to the inferior creatures of this world. We learn from him that St.

Gregory of Nazianzus, Origen and St. Cyril (the one, most likely, who refused

to see a human creature in Hypatia, and dealt with her as though she were a

wild animal) insisted that the word creatura, in the verses above quoted, was

applied by the Apostle simply to the angels! But, as remarks Cornelius, who

appeals to St. Thomas for corroboration, "this opinion is too distorted

and violent (distorta et violenta); it is moreover invalidated by the fact that

the angels, as such, are already delivered from the bonds of corruption."

Nor is St. Augustine's suggestion any happier; for he offers the strange

hypothesis that the "creatures," spoken of by St. Paul, were "the

infidels and the heretics" of all the ages! Cornelius contradicts the

venerable father as coolly as he opposed his earlier brother-saints.

"For," says he, "in the text quotedthe creatures spoken of by

the Apostle are evidently creatures distinct from men:--not only they but

ourselves also; and then, that which is meant is not deliverance from sin, but

from death to come."30 But even the brave Cornelius finally gets scared by

the general opposition and decides that under the term creatures St. Paul may

have meant--as St. Ambrosius, St. Hilarius (Hilaire) and others insisted

elements (!!) i.e., the sun, the moon, the stars, the earth, etc. etc.

Unfortunately

for the holy speculators and scholastics, and very fortunately for the

animals--if these are ever to profit by polemics--they are over-ruled by a

still greater authority than themselves. It is St. John Chrysostomus, already

mentioned, whom the Roman Catholic Church, on the testimony given by Bishop

Proclus, at one time his secretary, holds in the highest veneration. In fact

St. John Chrysostom was, if such a profane (in our days) term can be applied to

a saint,--the "medium" of the Apostle to the Gentiles. In the matter

of his Commentary on St. Paul's Epistles, St. John is held as directly inspired

by that Apostle himself, in other words as having written his comments at St.

Paul's dictation. This is what we read in those comments on the 3rd Chapter of

the Epistle to the Romans.

"We must

always groan about the delay made for our emigration(death); for if, as saith

the Apostle, the creature deprived of reason (mente, not anima,

"Soul")--and speech (nam si hæc creatura mente et verbo carens)

groans and expects, the more the shame that we ourselves should fail to do

so."3l

Unfortunately

we do, and fail most ingloriously in this desire for "emigration" to

countries unknown. Were people to study the scriptures of all nations and

interpret their meaning by the light of esoteric philosophy, no one would fail

to become, if not anxious to die, at least indifferent to death. We should then

make profitable use of the time we pass on this earth by quietly preparing in

each birth for the next by accumulating good Karma. But man is a sophist by

nature. And, even after reading this opinion of St. John Chrysostom--one that

settles the question of the immortal soul in animals forever, or ought to do so

at any rate, in the mind of every Christian,--we fear the poor dumb brutes may

not benefit much by the lesson after all. Indeed, the subtle casuist, condemned

out of his own mouth, might tell us, that whatever the nature of the soul in

the animal, he is still doing it a favour, and himself a meritorious action, by

killing the poor brute, as thus he puts an end to its "groans about the

delay made for its emigration" into eternal glory.

The writer is

not simple enough to imagine, that a whole British Museum filled with works

against meat diet, would have the effect of stopping civilized nations from

having slaughter-houses, or of making them renounce their beefsteak and

Christmas goose. But if these humble lines could make a few readers realize the

real value of St. Paul's noble words, and thereby seriously turn their thoughts

to all the horrors of vivisection--then the writer would be content. For verily

when the world feels convinced--and it cannot avoid coming one day to such a

conviction--that animals are creatures as eternal as we ourselves, vivisection

and other permanent tortures, daily inflicted on the poor brutes, will, after

calling forth an outburst of maledictions and threats from society generally,

force all Governments to put an end to those barbarous and shameful practices.

H.P. BLAVATSKY

Theosophist,

January, February,

and March, 1886

l De la

Resurrection et du Miracle. E. de Mirville.

2 De la Resurrection

et du Miracle. E. de Mirville.

3 Compare

also the difference between the translation of the same verse in the Vulgata,

and the texts of Luther and De Wette.

4 Commen.

Apocal., ch. v. 137.

5 It is but

justice to acknowledge here that De Mirville is the first to recognize the

error of the Church in this particular, and to defend animal life, as far as he

dares do so.

6 De

Beatificatione, etc., by Pope Benedict XIV.

7 In

scholastic philosophy, the word "form" applies to the immaterial

principle which informs or animates the body.

8 De

Beautificatione. etc. I, IV, c. Xl, Art. 6.

9 Quoted by

Cardinal de Ventura in his Philosophie Chretienne, Vol. 11, p. 386. See also De

Mirville, Résurrections animales.

10 Summa--Drioux

edition in 8 vols.

11 St.

Patrick, it is claimed, has Christianized "the most Satanized country of

the globe--Ireland, ignorant in all save magic"--into the "Island of

Saints," by resurrecting "sixty men dead years before."

Suscitavit sexaginta mortuos (Lectio I. ii, from the Roman Breviary, 1520). In

the M.S. held to be the famous confession of that saint, preserved. in the

Salisbury Cathedral (Descript. Hibern. I. II, C. 1), St. Patrick writes in an

autograph letter: "To me the last of men, and the greatest sinner, God

has, nevertheless, given, against the magical practices of this barbarous

people the gift of miracles, such as had not been given to the greatest of our

apostles--since he (God) permitted that among other things (such as the

resurrection of animals and creeping things) I should resuscitate dead bodies

reduced to ashes since many years." Indeed, before such a prodigy, the

resurrection of Lazarus appears a very insignificant incident.

12 More

recently Dr. Romanes and Dr. Butler have thrown great light upon the subject.

13

Biographie Universelle, Art. by Cuvier on Buffon's Life.

14 Discours

sur la nature des Animaux.

15 Esprits,

2m. mem. Ch. XII, Cosmolatrie.

16 Ibid.

17

Esprits--p. 158.

18 Longevity,

pp. 49 and 52.

19

Resurrections. p. 621.

20 The

occultists call it "transformation" during a series of lives and the

final, nirvanic Resurrection.

2l Leibnitz.

Opera philos., etc.

22 See vol.

XXIX of the Bibliothéque des sciences, 1st Trimester of the year 1768.

23 From two

Greek words--to be born and reborn again.

24 See Vol.

II Palingenesis. Also, De Mirville's Resurrections.

25 We too

believe in "future states" for the animal from the highest down to

the infusoria--but in a series of rebirths, each in a higher form, up to man

and then beyond --in short, we believe in evolution in the fullest sense of the

word.

26 See Isis,

Vol. I.

27 What was

really meant by the "sons of God" in antiquity is now demonstrated

fully in the SECRET DOCTRINE in its Part I (on the Archaic Period)--now nearly

ready.

28 This is

the orthodox Hindu as much as the esoteric version. In his Bangalore Lecture

"What is Hindu Religion?"--Dewan Bahadoor Raghunath Rao, of Madras,

says: "At the end of each Manvantara, annihilation of the world takes

place; but one warrior, seven Rishis, and the seeds are saved from destruction.

To them God (or Brahm) communicates the Statute law or the Vedas . . . as soon

as a Manvantara commences these laws are promulgated . . . and become binding .

. . to the end of that Manvantara. These eight persons are called Sishtas, or

remnants, because they alone remain after the destruction of all the others.

Their acts and precepts are, therefore, known as Sishtacar. They are also

designated 'Sadachar' because such acts and precepts are only what always

existed."

This is the

orthodox version. The secret one speaks of seven Initiates having attained

Dhyanchohanship toward the end of the seventh Race on this earth, who are left

on earth during its "obscuration" with the seed of every mineral,

plant, and animal that had not time to evolute into man for the next Round or

world-period. See Esoteric Buddhism, by A. P. Sinnett, Fifth Edition, Annotations,

pp. 146, 147.

29 . . .

ingemiscit et parturit usque adhuc in the original Latin translation.

30

Cornelius, edit. Pelagaud, I. IX, p.114.

31 Homélie

XIV. Sur l'Epitre aux Romains.

______________________

Cardiff

Theosophical Society in

Theosophy

House

206

Newport Road, Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 -1DL

Find out

more about

Theosophy

with these links

The Cardiff Theosophical Society Website

The National Wales Theosophy Website

If you

run a Theosophy Group, please feel free

to use

any of the material on this site

The Most Basic Theosophy

Website in the Universe

A quick overview of Theosophy

and the Theosophical Society

If you run a Theosophy Group you

can use this as an introductory handout.

Theosophy Cardiff’s Instant Guide

One liners and quick explanations

H P Blavatsky is

usually the only

Theosophist that

most people have ever

heard of. Let’s

put that right

The Voice of the Silence Website

An Independent Theosophical Republic

Links to Free Online Theosophy

Study Resources; Courses,

Writings,

The main criteria

for the inclusion of

links on this

site is that they have some

relationship (however

tenuous) to Theosophy

and are

lightweight, amusing or entertaining.

Topics include

Quantum Theory and Socks,

Dick Dastardly and Legendary Blues Singers.

A selection of

articles on Reincarnation

Provided in

response to the large

number of enquiries

we receive at

Cardiff

Theosophical Society on this subject

The Voice of the Silence Website

This is for everyone, you don’t have to live

in Wales to make good use of this Website

No

Aardvarks were harmed in the

The Spiritual Home of Urban Theosophy

The Earth Base for Evolutionary Theosophy

A B C D EFG H IJ KL M N OP QR S T UV WXYZ

Complete Theosophical Glossary in Plain Text Format

1.22MB

________________

Preface

Theosophy and the Masters General Principles

The Earth Chain Body and Astral Body Kama – Desire

Manas Of Reincarnation Reincarnation Continued

Karma Kama Loka

Devachan

Cycles

Arguments Supporting Reincarnation

Differentiation Of Species Missing Links

Psychic Laws, Forces, and Phenomena

Psychic Phenomena and Spiritualism

Quick Explanations

with Links to More Detailed Info

What is Theosophy ? Theosophy Defined (More Detail)

Three Fundamental Propositions Key Concepts of Theosophy

Cosmogenesis Anthropogenesis Root Races

Ascended Masters After Death States

The Seven Principles of Man Karma

Reincarnation Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

Colonel Henry Steel Olcott William Quan Judge

The Start of the Theosophical

Society

History of the Theosophical

Society

Theosophical Society Presidents

History of the Theosophical

Society in Wales

The Three Objectives of the

Theosophical Society

Explanation of the Theosophical

Society Emblem

The Theosophical Order of

Service (TOS)

Glossaries of Theosophical Terms

Index of

Searchable

Full Text

Versions of

Definitive

Theosophical

Works

H P Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine

Isis Unveiled by H P Blavatsky

H P Blavatsky’s Esoteric Glossary

Mahatma Letters to A P Sinnett 1 - 25

A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom

(Selection of Articles by H P Blavatsky)

The Secret Doctrine – Volume 3

A compilation of H P Blavatsky’s

writings published after her death

Esoteric Christianity or the Lesser Mysteries

The Early Teachings of The Masters

A Collection of Fugitive Fragments

Fundamentals of the Esoteric Philosophy

Mystical,

Philosophical, Theosophical, Historical

and Scientific

Essays Selected from "The Theosophist"

Edited by George Robert Stow Mead

From Talks on the Path of Occultism - Vol. II

In the Twilight”

Series of Articles

The In the

Twilight” series appeared during

1898 in The

Theosophical Review and

from 1909-1913

in The Theosophist.

compiled from

information supplied by

her relatives

and friends and edited by A P Sinnett

Letters and

Talks on Theosophy and the Theosophical Life

Obras

Teosoficas En Espanol

Theosophische

Schriften Auf Deutsch

An Outstanding

Introduction to Theosophy

By a student of

Katherine Tingley

Elementary Theosophy Who is the Man? Body and Soul

Body, Soul and Spirit Reincarnation Karma

Guide to the

Theosophy

Wales King Arthur Pages

Arthur draws

the Sword from the Stone

The Knights of The Round Table

The Roman Amphitheatre at Caerleon,

Eamont Bridge, Nr Penrith, Cumbria, England.

Geoffrey of Monmouth

(History of the Kings of Britain)

The reliabilty of this work has long been a subject of

debate but it is the first definitive account of Arthur’s

Reign

and one which puts Arthur in a historcal context.

and his version’s political agenda

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth

The first written mention of Arthur as a heroic figure

The British leader who fought twelve battles

King Arthur’s ninth victory at

The Battle of the City of the Legion

King Arthur ambushes an advancing Saxon

army then defeats them at Liddington Castle,

Badbury, Near Swindon, Wiltshire, England.

King Arthur’s twelfth and last victory against the Saxons

Traditionally Arthur’s last battle in which he was

mortally wounded although his side went on to win

No contemporary writings or accounts of his life

but he is placed 50 to 100 years after the accepted

King Arthur period. He refers to Arthur in his inspiring

poems but the earliest written record of these dates

from over three hundred years after Taliesin’s death.

Pendragon Castle

Mallerstang Valley, Nr Kirkby Stephen,

A 12th Century Norman ruin on the site of what is

reputed to have been a stronghold of Uther Pendragon

From wise child with no

earthly father to

Megastar of Arthurian

Legend

History of the Kings of Britain

Drawn from the Stone or received from the Lady of the Lake.

Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur has both versions

with both swords called Excalibur. Other versions

5th & 6th Century Timeline of Britain

From the departure of the Romans from

Britain to the establishment of sizeable

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

Glossary of

Arthur’s uncle:- The puppet ruler of the Britons

controlled and eventually killed by Vortigern

Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. Circa 450CE

An alleged massacre of Celtic Nobility by the Saxons

History of the Kings of Britain

Athrwys / Arthrwys

King of Ergyng

Circa 618 - 655 CE

Latin: Artorius; English: Arthur

A warrior King born in Gwent and associated with

Caerleon, a possible Camelot. Although over 100 years

later that the accepted Arthur period, the exploits of

Athrwys may have contributed to the King Arthur Legend.

He became King of Ergyng, a kingdom between

Gwent and Brycheiniog (Brecon)

Angles under Ida seized the Celtic Kingdom of

Bernaccia in North East England in 547 CE forcing

Although much later than the accepted King Arthur

period, the events of Morgan Bulc’s 50 year campaign

to regain his kingdom may have contributed to

Old Welsh: Guorthigirn;

Anglo-Saxon: Wyrtgeorn;

Breton: Gurthiern; Modern Welsh; Gwrtheyrn;

*********************************

An earlier ruler than King Arthur and not a heroic figure.

He is credited with policies that weakened Celtic Britain

to a point from which it never recovered.

Although there are no contemporary accounts of

his rule, there is more written evidence for his

existence than of King Arthur.

How Sir Lancelot slew two giants,

From Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur

How Sir Lancelot rode disguised

in Sir Kay's harness, and how he

From Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur

How Sir Lancelot jousted against

four knights of the Round Table,

From Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur

Try

these if you are looking for a local

Theosophy

Group or Centre

UK Listing of Theosophical Groups

Cardiff

Theosophical Society in Wales

206 Newport Road, Cardiff, Wales, UK. CF24 -1DL